Long-term (1-year) experience with LDS 100 in the treatment of men and women with androgenetic alopecia

Background. LDS 100 is

indicated for the treatment of men

and women with androgenetic alopecia

(male pattern hair loss, MPHL and

female pattern hair loss, FPHL).

However, the long-term (> 1 year)

efficacy of LDS 100 in this

population has not been previously

reported.

Objectives.

To assess the efficacy and safety of

LDS 100 in men and women with

androgenetic alopecia compared to

treatment with placebo device over 1

year.

Methods.

In 6 months, 240 men with MPHL and

80 women with FPHL were randomized

to receive LDS 100 treatment or

placebo treatment. Men and women

continued in up to 1 year, placebo

controlled extension studies.

Efficacy was evaluated by hair

counts, patient and investigator

assessments, and panel review of

clinical photographs.

Results.

Treatment with LDS 100 led to

durable improvements in scalp hair

over 1 year (p < 0.001 versus

placebo, all endpoints), while

treatment with placebo led to

progressive hair loss. LDS 100 was

generally well tolerated and no new

safety concerns were identified

during long-term use.

Conclusions.

In men with MPHL and in women with

FPHL, long-term treatment with LDS

100 over 1 year was well tolerated,

led to durable improvements in scalp

hair growth, and slowed the further

progression of hair loss that

occurred without treatment.

Androgenetic alopecia (male pattern hair loss, MPHL and female pattern hair loss, FPHL) occurs in men and women with an inherited sensitivity to the effects of androgens on scalp hair. The disorder is characterized by loss of visible hair over areas of the scalp due to progressive miniaturization of hair follicles. MPHL does not occur in men whit genetic deficiency of the type 2 5α-reductase (5αR) enzyme, which converts testosterone (T) to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), implicating DHT in the pathogenesis of this condition. Of the two 5αR isoenzymes in man, Type 1 predominates in sebaceous glands of the skin, including scalp, while Type 2 is present in hair follicles, as well as the prostate. In the androgenetic alopecia also occurs a reduction of the synthesis of the mRNA and the DNA with diminution of the cellular metabolism.

Three streets

of control of the hair growth exist:

- steroid control (T, 5αR, DHT);

- metabolic control (blood

circulation, glucose, ATP);

- autocrine-paracrine control (HrGF

- Hair Grow Factor).

The infrared radiation of LDS 100 (940 nm) penetrates in depth. It transits without producing great photo-biological effects; if not there where it comes to be absorbed then in the interface between the epidermis and the dermis. The photo-biological bases of therapeutic use of infrared radiation re-engage themselves in a mechanism “fallen” on various structures. There is a photoreception at the mitochondrial level. The radiation is absorbed at the level of the respiratory chain (cytochromes, oxidase cytocrome, dehydrogenase flowin) with the consequent activation of the respiratory chain and further the activation of the NAD (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide).

At the

cellular membrane level there is an

increase in the activity of the

enzyme Na/K ATPasis, which in turn

acts on the flow of Ca+. At this

point one has a transduction and an

amplification of the stimulus in the

cellular ambit, with the activation

of the cyclical nucleotides which

modulate the synthesis of the mRNA

and the DNA.

The final photo-response is the

bio-stimulation at the various

levels of the cellular metabolic

structure. The biological activation

spreads from cell to cell with

chemical transmissions. The infrared

light increases the cellular

metabolism accompanied by an

augmentation of the capillary

vascular bed of the radiant zone

with an increase also in the supply

of oxygen.

Studies in man with MPHL and women

with FPHL showed that LDS 100 had

utility in this disorder.

Randomized placebo-controlled trials demonstrated that treatment whit LDS 100 produced significant improvements in scalp hair growth, slowed the further progression of hair loss that occurred without treatment and led to increased patient satisfaction with the appearance of their scalp hair.

LDS 100 use is contraindicated in women when they are or may potentially be pregnant and in subjects with pace-maker or other metallic devices, or those with acute phlebitis, serious arterial hypertension, neurogical illnesses, heightened cardiopathy, dermatitis and dermatosis.

Materials and methods

Study population

Men aged 18 to

50 years, whit mild to moderately

severe vertex MPHL according to a

modified Norwood/Hamilton

classification scale (II vertex, III

vertex, IV or V), were enrolled.

Women aged 18 to 50 years, with mild

to moderately severe vertex FPHL

according to a Ludwig classification

scale (I, II or III), were enrolled.

Principal exclusion criteria

included significant abnormalities

on screening physical examination or

laboratory evaluation, surgical

correction of scalp hair loss,

topical Minoxidil use within

one-year, use of drugs with

androgenetic or antiandrogenetic

properties, use of finasteride or

other 5αR inhibitors, or alopecia

due to other causes. Men and women

were instructed not to alter their

hairstyle or dye their hair during

the studies.

Study protocols

One initial, 6-months randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled studies were initiated, and both were continued as 1 consecutive, 6-months, double-bind, placebo-controlled extension studies. The objectives of the controlled extension studies were to determine the effect of long-term use of LDS 100, the effect of delaying treatment by one year, and the progression of MPHL in men and FPHL in women not receiving active treatment.

6-months initial studies

Following a screening procedure,

study subjects entered a 2 week,

single-blind, placebo run-in period.

All men and women received study

shampoo (Claim 3S®) for

standardization of shampoo used and

for prophylaxis of seborrheic

dermatitis, which might affect scalp

hair growth. Subjects (240 men and

80 women) were than randomized to

LDS 100 (2 times for week, 20

minutes, 140 Hz) or placebo LDS 100

(no infrared light, 2 times for

week, 20 minutes, 140 Hz) (1:1) for

six months (Figs. 1 and 2).

Men and women visited the clinic

every 3 months, where they completed

a hair growth questionnaire and

investigators completed assessments

of scalp hair growth.

Every 6 months, photographs of scalp

hair were taken for hair counts and

for the expert panel assessments of

hair growth. Reports of adverse

events were collected throughout the

studies.

6-months extension studies

Men and women completing the initial

6-months, placebo controlled studies

were eligible to enrol in one

consecutive, 6-months,

placebo-controlled extension studies.

In these extension studies, men (N =

183) and women (N = 55) were

randomly assigned (as determined at

initial randomization) to treatment

with either LDS 100 (2 times for

week, 20 minutes, 140 Hz) or placebo

LDS 100 (no infrared light, 2 times

for week, 20 minutes, 140 Hz) (9:1),

such that subjects were randomized

to one of four groups that allocated

treatment to them during both the

initial 6-months studies and the

6-months extension studies:

LDS 100

LDS

100, LDS 100

LDS

100, LDS 100

Placebo,

Placebo,

Placebo  LDS 100, or Placebo

LDS 100, or Placebo

Placebo.

Placebo.

The procedures for the 6-months extension studies were similar to those for the initial 6-months studies.

Efficacy measurements

Four predefined efficacy endpoints

provided a comprehensive assessment

of changes in scalp hair from

baseline:

(1) hair counts, obtained from color

macrophotographs of a 1-inch

diameter circular area (5.1 cm2) of

clipped hair (length 1 mm), centered

at the anterior leading edge of the

vertex thinning area;

(2) patient self-assessment of scalp

hair, using a validated,

self-administered hair growth

questionnarie;

(3) investigator assessment of scalp

hair growth, using a standardized

7-point rating scale;

(4) independent assessment of

standardized clinical global

photographs of the vertex scalp by a

panel of dermatologists who were

blinded to treatment and experienced

in photagraphic assessment of hair

growth, using the standardized

7-point rating scale.

Safety

measurements

Safety measurements included

clinical and laboratory evaluations,

and adverse experience reports.

A data

analysis, plan pre-specified all

primary and secondary hypotheses,

including combining data from the

initial 6-months studies to improve

precision of the estimates of the

treatment effect, as well as from

each of the 6-months controlled

extensions due to the small size of

the placebo groups in those studies.

Hair counts were assessed by the

difference between the count at each

time point versus the baseline count,

and mean hair count values for each

treatment group were determined

using SASTM Least Squares Means.

Each of the seven questions in the

patient self-assessment of hair

growth was assessed separately, and

the responses to each question at

each time point were taken as

assessments of changes from baseline.

The investigator assessment of hair

growth and the expert panel

assessments of global photographs

were assessed by comparison of mean

rating scores for each tratment

group at each time point, based on

the 7-point rating scale (minimum

value = -3.0 [greatly decreased];

maximum value = 3.0 [greatly

increased].

Hypothesis testing for hair counts,

individual patient self-assessment

questions, and investigator and

global photographic assessments was

performed using analysis of variance.

The primary efficacy analysis

population for this report was the

intention to treat population, which

included all subjects with at least

one day randomozed therapy and with

both baseline and at least one

post-baseline efficacy assessment.

For all efficacy analyses, missing

data were estimated by carring data

forward from the previous visit.

However, no data were carried

forward from the baseline evaluation,

or between the initial 6-months

study and the 6-months extension

study.

A secondary population for analysis

of efficacy included only the data

from the cohort of subjects who

completed the 1-year study.

Safety analyses were based on all

subjects with at least one day of

randomized therapy. The safety

analyses focused on the biochemical

parameters, using analysis of

variance, and on adverse experience

reports.

Results

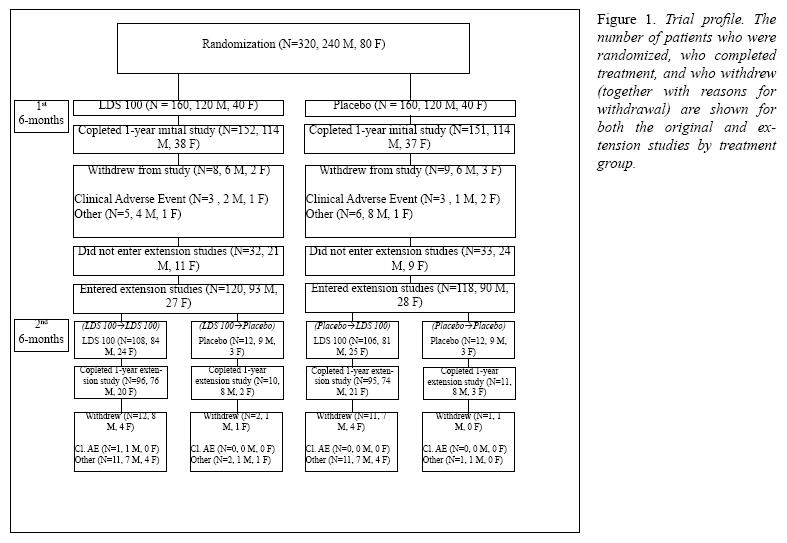

Patient accounting and baseline characteristicsPatient accounting is summarized in Figure 1. A summary of baseline characteristics for man and women who entered the extension study (2nd 6-months) is presented by treatment group in Table I. Demographics and baseline caharacteristics were comparable among the four treatment groups.

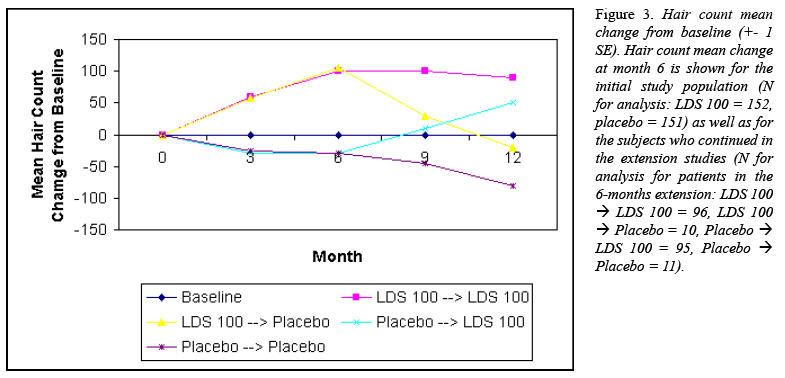

Hair countsIn the group

that received LDS 100 for all 12

months (LDS 100

LDS

100), there were significant

increases in hair counts over 1 year

(p < 0.001 versus baseline for all

time points), which reached a

maximal increase at month 6,

declined somewhat thereafter but

remained above baseline throughout,

with a mean increase of hairs at

month 12 (Fig. 3).

LDS

100), there were significant

increases in hair counts over 1 year

(p < 0.001 versus baseline for all

time points), which reached a

maximal increase at month 6,

declined somewhat thereafter but

remained above baseline throughout,

with a mean increase of hairs at

month 12 (Fig. 3).

In contrast,

in the group that received placebo

for all 12 months (Placebo

Placebo), there was a progressive

decline in hair counts over 1 year,

culminating in a mean decrease from

baseline of hairs at month 12 (Fig.

3).

Placebo), there was a progressive

decline in hair counts over 1 year,

culminating in a mean decrease from

baseline of hairs at month 12 (Fig.

3).

For the group

crossed over from Placebo to LDS 100

after 6 months (Placebo

LDS

100) there was a decrease in hair

count during the months of placebo

treatment. This initial loss of hair

on placebo was followed by

significant increases in hair count

during treatment with LDS 100

through month 12 (Fig. 3). Increases

in hair count during LDS 100

treatment in this group were

generally sustained over time,

although the increases compared to

baseline were consistently less than

those observed in the LDS 100

LDS

100) there was a decrease in hair

count during the months of placebo

treatment. This initial loss of hair

on placebo was followed by

significant increases in hair count

during treatment with LDS 100

through month 12 (Fig. 3). Increases

in hair count during LDS 100

treatment in this group were

generally sustained over time,

although the increases compared to

baseline were consistently less than

those observed in the LDS 100

LDS 100

group at comparable time points,

with the difference being similar in

magnitude to the amount of hair loss

sustained during the year of placebo

treatment.

LDS 100

group at comparable time points,

with the difference being similar in

magnitude to the amount of hair loss

sustained during the year of placebo

treatment.

For the group

that received LDS 100 for 1st 6

months, was crossed over to placebo

for 2nd 6 months (LDS 100

Placebo), the beneficial effect on

hair count seen during the first

6-months of LDS 100 treatment was

reversed after 6 months of placebo

treatment (Fig. 3).

Placebo), the beneficial effect on

hair count seen during the first

6-months of LDS 100 treatment was

reversed after 6 months of placebo

treatment (Fig. 3).

For each of

the seven questions in the patient

self-assessment questionnaire,

treatment with LDS 100 (LDS 100

LDS

100) was superior to treatment with

placebo (Placebo

LDS

100) was superior to treatment with

placebo (Placebo

Placebo) at each time point (p <

0.001 for all between-group

comparisons).

Placebo) at each time point (p <

0.001 for all between-group

comparisons).

The LDS 100

LDS 100

group demonstrated significant (p <

0.001) improvement from baseline at

each time point for each question,

with the exception that there was no

significant difference from baseline

at the month 6 time point for

Question 5a (assessment of

satisfaction with appearance of the

frontal hairline), where as the

Placebo

LDS 100

group demonstrated significant (p <

0.001) improvement from baseline at

each time point for each question,

with the exception that there was no

significant difference from baseline

at the month 6 time point for

Question 5a (assessment of

satisfaction with appearance of the

frontal hairline), where as the

Placebo  Placebo group generally demonstrated

deterioration from baseline over

time.

Placebo group generally demonstrated

deterioration from baseline over

time.

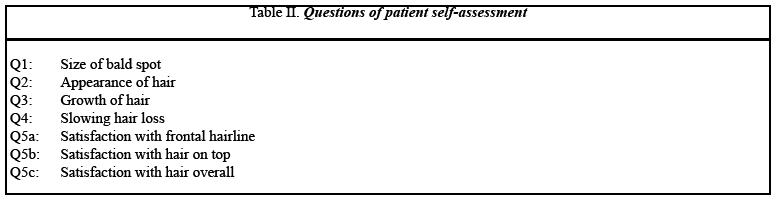

For each of the seven questions, a greater proportion of LDS 100- versus placebo-trated subjects reported an improvement from baseline, with the difference between groups increasing over time (Table II).

In the Placebo

LDS 100

group, there was generally sustained

improvement following 6 months of

placebo treatment for each question

during the period of LDS 100

treatment (p < 0.001), although, as

with hair counts, this improvement

was less than that seen in the LDS

100

LDS 100

group, there was generally sustained

improvement following 6 months of

placebo treatment for each question

during the period of LDS 100

treatment (p < 0.001), although, as

with hair counts, this improvement

was less than that seen in the LDS

100  LDS

100 group at comparable time points.

LDS

100 group at comparable time points.

For the LDS

100  Placebo group, partial to complete

reversibility of the beneficial

effect of LDS 100 was observed for

six of the seven questions after 6

months of placebo treatment (2nd

6-months).

Placebo group, partial to complete

reversibility of the beneficial

effect of LDS 100 was observed for

six of the seven questions after 6

months of placebo treatment (2nd

6-months).

Based on the

investigator assessment, treatment

with LDS 100 (LDS 100

LDS

100) was superior to treatment with

placebo (Placebo

LDS

100) was superior to treatment with

placebo (Placebo

Placebo) at each time point (p <

0.001, all comparisons).

Placebo) at each time point (p <

0.001, all comparisons).

The Placebo

LDS 100

group showed improvement during the

period of LDS 100 therapy, although

as with hair counts and patient

self-assessment the magnitude of

this improvement was less than that

seen in the LDS 100

LDS 100

group showed improvement during the

period of LDS 100 therapy, although

as with hair counts and patient

self-assessment the magnitude of

this improvement was less than that

seen in the LDS 100

LDS 100

group at comparable time points.

LDS 100

group at comparable time points.

For the LDS 100

Placebo

group, there was initial improvement

during the first year of LDS 100

treatment, followed by a plateau

during the 6-months of placebo

treatment.

Placebo

group, there was initial improvement

during the first year of LDS 100

treatment, followed by a plateau

during the 6-months of placebo

treatment.

Based on the

global photographic assessment,

treatment with LDS 100 (LDS 100

LDS

100) was superior to treatment with

placebo (Placebo

LDS

100) was superior to treatment with

placebo (Placebo

Placebo) at each time point (p <

0.001, all comparisons).

Placebo) at each time point (p <

0.001, all comparisons).

At month 12, 48% of LDS 100-treated subjects were rated as slightly, moderately, or greatly improved compared to 6% of placebo-treated subjects.

Viewed in the

context of maintaining visible hair

from baseline, 90% of subjects

treated with LDS 100 demonstrated no

further visible hair loss by this

assessment, compared to 25% of

patients on placebo.

Conversely, 75% of subjects treated

with placebo demonstrated futher

visible hair loss by this assessment

at 1 year, compared to 10% of

subjects on LDS 100 (Fig. 5).

For the LDS

100  LDS

100 group, maximal improvement by

global photographic assessment was

observed at month 12.

LDS

100 group, maximal improvement by

global photographic assessment was

observed at month 12.

In contrast,

the Placebo

Placebo

group demonstrated progressive

worsening by global photographic

assessment through month 12.

Placebo

group demonstrated progressive

worsening by global photographic

assessment through month 12.

The Placebo

LDS 100

group also demonstrated sustained

improvement in mean score during the

period of LDS 100 treatment from

month 6 to month 12 (p < 0.001),

although, as with the three other

efficacy measures, the magnitude of

improvement was less than that seen

in the LDS 100

LDS 100

group also demonstrated sustained

improvement in mean score during the

period of LDS 100 treatment from

month 6 to month 12 (p < 0.001),

although, as with the three other

efficacy measures, the magnitude of

improvement was less than that seen

in the LDS 100

LDS 100

group for comparable time points.

LDS 100

group for comparable time points.

For the

Placebo  LDS 100 group, the beneficial effect

of LDS 100 was reversed after 6

months of placebo treatment (p <

0.001).

LDS 100 group, the beneficial effect

of LDS 100 was reversed after 6

months of placebo treatment (p <

0.001).

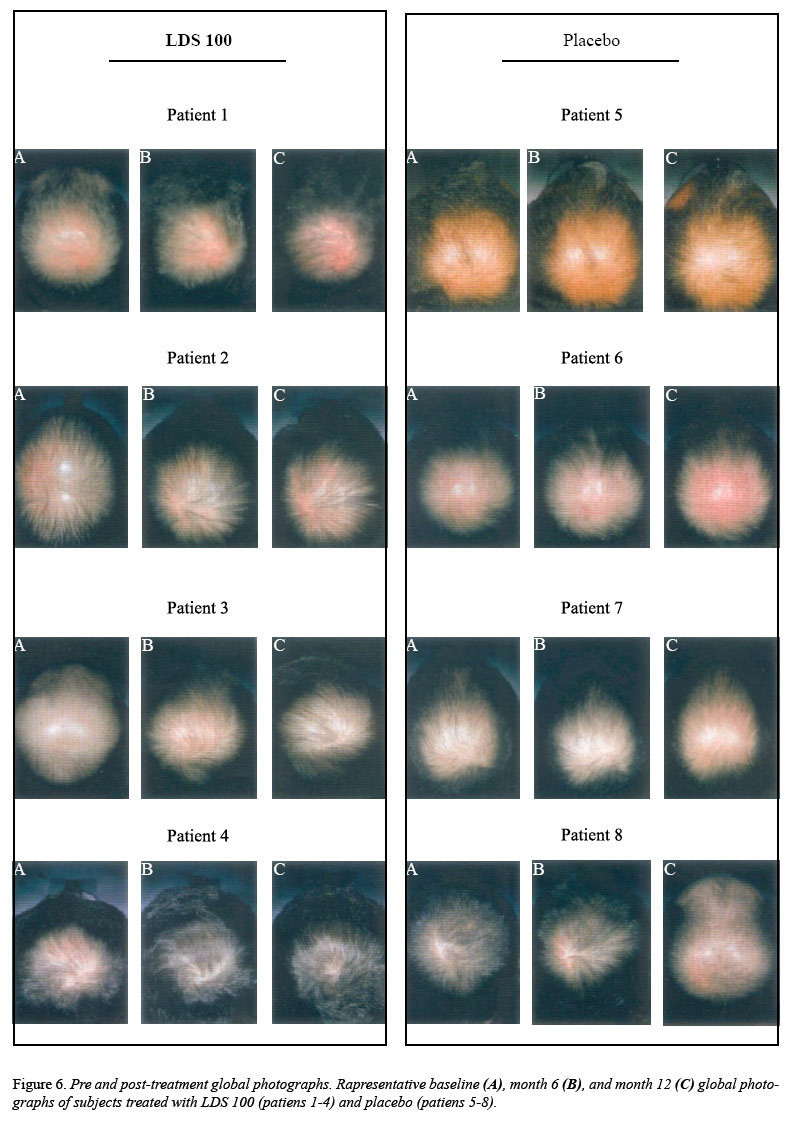

Global

photographs of representative

subjects from the Placebo

Placebo

and LDS 100

Placebo

and LDS 100

LDS 100

groups who were rated by the expert

panel as having decreased or

increased hair growth from baseline

are shown in Figure 6.

LDS 100

groups who were rated by the expert

panel as having decreased or

increased hair growth from baseline

are shown in Figure 6.

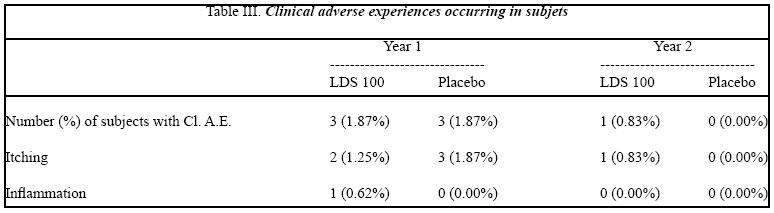

Clinical adverse experiences that were considered by the investigator to be possibly or definitely treatment-related and that occurred in at least 1% of subjects are summarized in Table III.

As reported previously, in the first 6-months a slightly higher proportion of LDS 100 than placebo subjects reported treatment-related adverse experiences related to itching and inflammation (Table III), discontinued the studies due these side effects. These side effects resolved after discontinuation and also resolved in most subjects who reported them but remained on therapy with LDS 100. The adverse experience profile for subjects continuing in the extension studies was similar to that of the initial studies (Table III).

Discussion

The data from this study and its long-term extension represent the longest reported controlled observations in men with MPHL and women with FPHL.

The combined analysis demonstrated that long-term tretament with LDS 100 led to significant and durable improvements, compared to both baseline and placebo, in scalp hair in men with MPHL and in women with FPHL. Hair counts increased over the first 6-months of treatment with LDS 100, with improvement above baseline maintained over 1 year. In contrast, the placebo group progressively lost hair over 1 year, confirming the natural progression of hair loss in this disorder due to the conyinued miniaturization of scalp hair. Thus, the treatment effect of LDS 100 on hair count relative to placebo increased progressively over time, leading to a net improvement for LDS 100-treated subjects hairs compared to placebo at one year. Most (65%) LDS 100-treated subjects had increases in hair counts at one year, compared to none of the placebo-treated subjects, but even for those LDS 100-treated subjects with less hair by hair count at one year, the magnitude of loss was less than that observed in the placebo group. these data support that the progression of hair loss observed in placebo-treated subjects was significantly reduced by treatment with LDS 100.

Based on the predefined endpoints utilizing photographic methods (hair counts, and global photographic assessment), peak efficacy was observed at 6 months to 12 months of treatment with LDS 100. This observation of an apparent peaking effect is likely due, in part, to the previously-reported beneficial effects of LDS 100 on the hair growth cycle based on a phototrichogram study. In that study, initiation of LDS 100 treatment was shown to increase the number of anagen-phase hairs and to increase the anagen to telogen ratio, consistent with normalization of the growth cycles of previously miniaturized hairs.

Consistent with these results, LDS 100 treatment was also shown to increase the growth rate and/or thikness of hairs, based on analysis of serial hair weight measurements. Because these beneficial changes in the hair growth cycle are dependent on when therapy with LDS 100 is initiated and occur rapidly, the affected hairs are driven to cycle in a synchronous manner. If these hairs have somewhat similar anagen phase durations, they would enter telogen phase as the anagen (and catagen) phase ended, followed by subsequent shedding, in a partially synchronized fashion. This would be expected to produce a gradual decline from peak hair count after a period of time equal to the average anagen phase duration. Eventually, as subsequent growth cycles recurred, these hairs would be expected to become increasingly independent, thereby losing their synchronous character as their growth cycles further normalized over time, leading to a sustained increase in hair count at a plateau above baseline, as suggested by the 1 year data presented here.

Patient self-assessment of hair growth provides a mechanism for each subject to judge the benefits of treatment under controlled and blinded conditions. This questionnaire asks specific questions about the patient’s hair growth or loss and his degree of satisfaction with the appearance of his hair compared to study start. While a placebo effect was observed with this instrument, as is typical of patient questionnaire data, results consistently demonstrated that subjects treated with LDS 100 had a more positive self-assessment of their hair growth and satisfaction with their appearance than subjects treated with placebo, with the majority of LDS 100-treated subjects reporting satisfaction with the overall appearance of their scalp hair at 1 year. Consistent with the findings of another study in which LDS 100 was evaluated in subjects with predominantly frontal MPHL, patients’ satisfaction with the appearance of their frontal hairline was improved by treatment with LDS 100 in the present study.

The investigators’ assessment are based on observations of subjects seen in the clinic and provide a clinically relevant assessment of the patient’s hair growth or loss since study start. These assessments demonstrated a sustained benefit of LDS 100 treatment over 1 year.

As with the

patient self-assessment, the

investigator assessment had a

greater placebo effect than the more

objective

endpoints of hair count and global

photographic assessment. Such an

effect is not inusual in

double-blind, placebo-control led

studies, and is often due to general

expectation bias on the part of the

patient’s treating physician.

Despite this

apparent placebo effect, the

beneficial effects of LDS 100 were

demonstrated by the clinical

assessment made by the investigators

in these studies. In contrast to the

investigator assessment, the blinded

comparison of paired pre- and

post-treatment global photographs by

the expert panel, which also

assessed change from baseline,

demonstrated minimal, if any,

placebo effect.

Based on this assessment, LDS 100

treatment led to maintenance of

improvement above baseline in scalp

hair growth and scalp coverage over

one year, while placebo subjects

progressively worsened.

Treatment with LDS 100 for one year led to sustained protection against further visible hair loss in nearly all (90%) subjects, while further visible hair loss as evident in most (75%) subjects treated with placebo over the same time period.

While the number of patients remaining in the study declined over time and the size of the placebo group was limited in the extension study, the results of analyses that included either all available patients at each time point or only the cohort of patients with data at month 12 were consistent and supported a sustained benefit in hair growth for subjects receiving LDS 100 compared with placebo.

Additionally, examination of data from placebo-treated subjects in all cohorts demonstrated the continued loss of scalp hair that occurs in untreated subjects with MPHL and FPHL. Thus, regardless of the cohort examined, the long-term data from these studies consistently demonstrated a beneficial effect of LDS 100 compared with placebo for men with MPHL and women with FPHL.

Moreover, this beneficial effect increased over time due to the progressive increase in the net treatment effect of LDS 100 compared with placebo.

The safety data from the one year of controlled observations in the current study provide reassurance that long-term use of LDS 100 in men with MPHL and women with FPHL is not associated with an increase in the incidence of adverse experiences or any new safety concerns.

A few subjects in the current studies experienced reversible itching and inflammation. No other significant adverse effects of LDS 100 were observed in the patient population evaluated in the current studies.

This excellent

safety profile of long-term use of

LDS 100 is consistent with the

experience with the infrared light

at five times the dose used in the

present study that has been

well-documented in large clinical

trials and post-marketing

surveillance in men and women.

In summary, treatment with LDS 100

over one year increased scalp hair

as determined by scalp hair counts,

patient self-assessment,

investigator assessment, and global

photographic assessment, when

compared with placebo. In contrast,

data from the placebo group

confirmed that without treatment

progressive reductions in hair count

and continued loss of visible hair

occurs.

Long-term

treatment with LDS 100 was generally

well tolerated. The results of these

studies demonstrate that chronic

therapy with LDS 100 leads to

durable improvements in hair growth

in men with MPHL and women with FPHL

and slows the further progression of

hair loss that occurs without

treatment.

References

1. Arndt

K.A., Noe I.M. et al.: Laser Therapy.

Basic concepts and nomenclature. J.

am. Acad. Dermatol. Dec. 1981, 5

2. Dwyer R.M., Bass M.: Laser

Applications. Vol. III Monte Ross

Ed. Academic press, N.Y., 1977.

3. Fine S., Klein E.: Interaction of

laser radiation with biological

system. Proceeding of the first

Conference on Biologic effects of

laser radiations. Fed. Proc., 24,

35, 1965.

4. Goldman L.: Effects of new laser

systems on the skin. Arch. Dermat..,

108, 385, 1973.

5. Goldman L.: Applications of the

Laser. Cleveland. Chemical Rubber

Co., 1973.

6. IIda H., Takahara H., Kahehi H.,

Tateno Y., Mammoto M.: Fundamental

studies on laser radiation therapy.

Nippon Acta radiol., 1969, Jul., 29,

411-5.

7. Mester E., Ludany G., Sellyei M.,

Szende B., Tota J.: The stimulating

effect of power laser rays on

biological systems. Laser Rev., 1,

3, 1968.

8. Mester E. et al.: Experimental

and clinical observations wih Laser.

Panmin. Med., 13, 538, 1971.

9. Olsen EA: Androgenetic alopecia.

In: Olsen EA, ed. Disorders of hair

growth: diagnosis and treatment. New

York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1994:

257-83.

10. Price VH: Testosterone

metabolism in the skin. Arch.

Dermatol. 1975; 111: 1496-502.

11. Wolbarsht M.L.: Laser

applications in medicine and biology.

Vol. 1-2 Plenum Press. N.Y.,

1971/74.

Table I. Baseline characteristics of

subjects entering the extension

study